Understanding the Audio Compact Cassette

Understand the audio cassette tape technology (audio cassettes), what they were, their impact and how the technology worked in our comprehensive guide.

Audio Compact Cassette includes:

Audio compact cassette basics

Few objects evoke such potent nostalgia as the humble audio cassette. It played an enormous part in the lives of us all in the 1970s and 1980s.

The small, rectangular shells, once ubiquitous symbols of portable sound, hold within them a story of technological innovation, cultural revolution, and the enduring allure of analog magic.

Today, in the age of streaming services and digital downloads, the cassette may seem like a relic, but its impact on music, technology, and even our personal memories remains undeniable.

The analogue audio cassette provided a step forward over vinyl in terms of portability, durability, and general ease of use at the time.

The birth of the cassette

Born in 1963 from the mind of Dutch inventor Lou Ottens, the cassette tape was initially envisioned as a tool for dictation, not music. Its compact size and ease of use quickly made it popular for recording meetings, lectures, and interviews.

But soon, its potential for music reproduction became apparent. The first commercially available music cassettes appeared in the late 1960s, offering an affordable and portable alternative to bulky vinyl records.

The 1970s saw the cassette's true ascent. The invention of the Sony Walkman in 1979 transformed music consumption, liberating it from living rooms and cars and placing it firmly in pockets and backpacks. Suddenly, everyone could carry their own soundtrack, creating personalised mixtapes that spoke to their tastes and memories.

Audio cassettes fuelled the rise of genres like punk, hip-hop, and independent music. Their affordability and easy duplication made them perfect for independent artists and small labels, fostering a DIY revolution in music creation and distribution.

Mixtapes became cultural currency, exchanged between friends and lovers, capturing the essence of a moment, a mood, or a shared passion.

The Inner Workings of the cassette

But what phenomena allowed these plastic rectangles to hold music? Inside each cassette lay a thin strip of magnetic tape, coated with microscopic iron oxide particles. This seemingly simple ribbon was the canvas upon which sound was painted.

During recording, electrical signals representing sound waves were sent to the recording head. This head generated a magnetic field that aligned the iron oxide particles in different patterns on the tape, each pattern corresponding to a specific sound frequency.

Playback was the reverse process. As the tape passed the playback head, the aligned particles induced a tiny electrical current that mimicked the original sound waves. These waves were then amplified and sent to speakers, bringing the music back to life.

The hiss, the pops, the occasional jam – these were not imperfections, but rather the inherent character of analog sound. Cassettes are said to capture not just the music, but the texture of the recording process itself, adding a layer of warmth and intimacy that digital audio often lacks. This is partly dues to the limitations of the tape as a recoding medium as it is not able to record the sound totally accurately and the warmth can be as a result of the limitations of the frequency response and attack time.

Cassette tape varieties

Although the vast majority of cassettes used were just the standard type, occasionally other types were seen. Some players / recorders might have a switch for the different types.

The different types had different levels of performance as well as different cost levels, suiting different budgets and users.

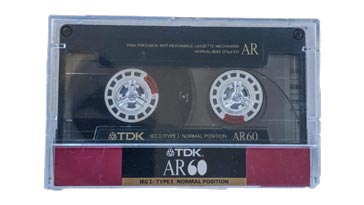

Three main types were available: Standard (Type I), Chrome (Type II), and Metal (Type IV). A fourth type known as Type III was introduced but was never widely manufactured and used.

Standard (Type I): This was what might be called the reliable workhorse of cassette tapes. They were the most common and affordable tapes, making them the first choice for users. Made with ferric oxide particles, they delivered quite a reasonable sound quality, especially for spoken word or less complex music. However, they had higher hiss levels and limited high-frequency response, making them less suitable for capturing the full spectrum of instruments and vocals for the real audio enthusiasts.

Chrome (Type II): The chrome tapes offered a better or sharper sound but at an increased price. Chrome tapes were the next level up and they offered increased sensitivity and improved high-frequency performance. They used chromium dioxide CrO2 particles in the tape itself, and this enabled a much better dynamic range, better high frequency response and less background hiss. This allowed for crisper cymbals, brighter vocals, and overall punchier and better overall fidelity of the sound. However, they required higher bias settings on recorders and were more expensive than standard tapes.

FerriChrome (Type III): In 1973, Sony introduced a hybrid form of cassette. They were advertised as the best of both words and comprised a five-micron ferric base coated with one micron of CrO2 pigment. The new formulation provided the good low-frequency response of microferric tapes with good high-frequency performance of chrome tapes. However they failed to attract the market attention and never caught on.

Metal (Type IV): Metal tapes were the best type on offer and could be considered as the 'The King of Clarity and Fidelity.' This cassette technology, offered the nearest to CD-quality sound. They were made with metal particles like cobalt and iron, they boasted extremely low hiss, extended high and low-frequency response, and unmatched sonic accuracy. This made them ideal for capturing complex music genres and critical listening experiences. However, metal tapes were the most expensive, required specific bias settings, and could wear out recorder heads quicker due to their harder particles which made them more abrasive.

Tape lengths

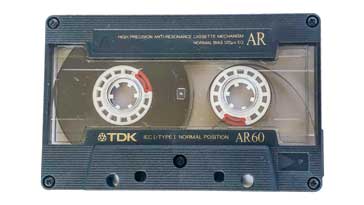

The cassette tapes were available in a variety of lengths. Normally they were standard lengths, and they were designated according to their total playing time, i.e. both sides or directions together.

They were typically designated by a capital letter C, followed by the time in minutes.

A variety of standard values were available, and to accommodate all the tape, the thickness of the actual tape varied according to the length.

The main tape lengths are:

C60 - 30 minutes playing per side: The C60 was one of the more popular sizes, and although only giving 30 minutes a side, it was robust, as it typically used 15 to 16 µm thick tape.

C90 - 45 minutes playing per side: The C90 was another very popular size, and being 45 minutes long each side, it often allowed for a complete vinyl album to be recorded on each side as they were normally shorter than 45 minutes for both sides of the disc. The tape used was typically around 10 to 11 µm as it was necessary to get a longer length into the cassette to give the longer playing time.

C120 - 60 minutes per side: This was generally the longest tape that was produced With the tape often being just 6µm thick, these tapes were prone to stretching and breaking. They also suffered occasionally from print-through where the magnetic variations on one turn of the tape were printed though onto the next. This was more prone to occur when the tape was left unused for a while as the different turns on the spool had longer in contact with each other.

Although these are the main lengths, very occasionally c180 tapes were available, but these were not to be recommended as they were very prone to stretching and breakage.

Other lengths were also available, but for different applications - C10, C12 and C15 were useful for early home computers data storage and for use in telephone answering machines. Other lengths that could be found were C30, C40, C50, C54, C64, C70, C74, C80, C84, C94, C100, C105, and C110. These were not common;y available and would need to be sourced from specialist suppliers.

The Rise of the Walkman

The 1979 release of Sony's Walkman was a pivotal moment. This portable cassette player, with its iconic yellow headphones, transformed music from a stationary experience to a mobile one. People could now take their music anywhere, soundtracking their commutes, workouts, and adventures. The cassette became a symbol of personal expression and freedom, its click-clack language and personalised mixtapes forming a shared cultural currency.

The cassette era saw the rise of audio tech giants like Sony, JVC, and Maxell, each vying for dominance with innovations like Dolby Noise Reduction and metal tapes that promised higher fidelity.

Blank tapes became blank slates for creativity, birthing the mixtape culture where friends curated personalised sonic journeys for each other. From punk rock anthems to bedroom ballads, mixtapes were intimate time capsules, echoing with shared memories and unspoken feelings.

Impact of the cassette beyond music

The cassette's influence extended far beyond music. It revolutionised language learning, democratised education through audio lectures, and became a vital tool for archiving oral histories and cultural traditions.

In developing countries, where access to electricity and technology was limited, cassettes became windows to the wider world, bringing news, information, and stories to remote communities.

Cassettes played a pivotal role in the rise of home audio recording. Four-track cassette recorders allowed aspiring musicians to experiment and create in their bedrooms, paving the way for countless bands and artists. And let's not forget the humble boombox, which transformed parks, beaches, and streets into open-air dance floors, fuelled by the infectious energy of shared playlists.

The audio cassette's decline and enduring legacy

The arrival of CDs and digital formats in the late 1980s and 1990s marked the beginning of the cassette's decline. CDs offered cleaner sound, skip-free playback, and the ability to store more music. Downloads and streaming services later made music even more accessible and portable, seemingly rendering the cassette obsolete.

Yet, the cassette never truly faded away. A niche market thrives, fuelled by vintage enthusiasts, audiophiles who appreciate the warmth of analog sound, and musicians who embrace the lo-fi aesthetic of cassette recordings.

Today, many artists from diverse genres release their music on cassette as a statement of artistic choice and a connection to the music's historical roots.

The legacy of the cassette tape is not simply about a format, but about the cultural and emotional connections it forged.

Instead it was a democratising force, putting music in the hands of listeners and creators alike. It was a catalyst for creativity, a canvas for mixtapes and home recordings that captured the essence of a time and place.

And beyond its technological function, the cassette became a symbol of personal expression, shared experiences, and the enduring power of analog magic.

So, the next time you stumble upon an old cassette tape, don't dismiss it as a relic. Hold it in your hand, remember the music it held, and the stories it whispered. For within that small plastic shell lies a testament to human ingenuity, a reminder of the way in which music could be enjoyed everywhere.

Written by Ian Poole .

Written by Ian Poole .

Experienced electronics engineer and author.

More Audio Video Topics:

HDMI

SCART

DisplayPort

DVI

Loudspeaker technology

Headphones & earphones

Bluetooth speakers

Stereo sound

Microphones

Audio compact cassettes

Vinyl record technology

Digital radio

DVB television

Return to Audio / Video menu . . .