Michael Faraday Biography

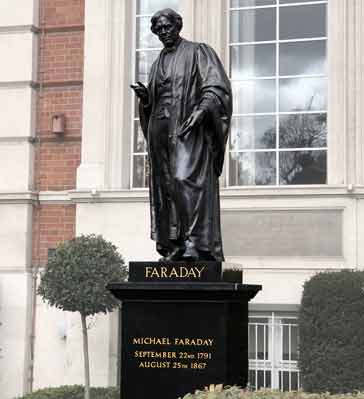

Michael Faraday was one of the greatest scientists of all time and yet he received little formal education - during his life he made many discoveries associated with electrical science and chemistry.

Michael Faraday Biography Includes:

Michael Faraday

Discoveries & inventions

Facts & quotes

Called the Father of Electrical Engineering and the greatest scientist of his day, Michael Faraday came from a humble background and received little formal education. In his lifetime Faraday achieved a great amount in many spheres of scientific discovery whilst also being a brilliant and charismatic lecturer.

Michael Faraday is best known for formulating the laws of electromagnetic induction, and laying the foundations necessary to make electric motors, dynamos and transformers. On top of this he devised the laws of electrolysis, was the first to liquefy chlorine, to isolate benzene and he also discovered magneto-optical effects. Through all of this he was a deeply religious and humble man whose scientific knowledge and religious beliefs were in harmony.

With him coming from a humble background and receiving little education, the story of Michael Faraday's life shows how it is possible to achieve great things, even without a high class education.

Faraday's Birth

Michael Faraday was born on 22nd September 1791 in Newington Butts, an area now covered by the Elephant and Castle, just south of the River Thames in London. His father, James Faraday was a blacksmith from Westmorland but a few years before Faraday's birth he had moved to London.

Faraday's father was also a member of the Sandemanian sect of the Christian Church, and this had a profound effect on Michael Faraday's adult life. Not only were the Sandemanians strict Christians, but they also encouraged their members to read - it was important to be able to read the Bible. Accordingly Faraday became an avid reader, a factor that enabled him to educate himself later.

At school the young Michael Faraday only learned the rudiments of reading writing and arithmetic, and then at the age of fourteen in 1805, he was apprenticed to George Reibau as a bookbinder. Here he was able to read many books and improve his standard of education. He read many scientific books, and he also repeated many of the experiments on his own, even building his own electrostatic machine. He also joined the City Philosophical Society in 1810, the place where he was to give his first lectures. Aware of his need to improve himself, he persuaded a friend to tutor him in grammar for two hours a week, an arrangement that continued for seven years!

In 1812, a customer who cam into the bookshop where Faraday worked asked him if he would like some tickets to listen to lectures by Sir Humphrey Davy of the Royal Institution - at the time, Davy was one of the world's leading scientists. He attended the lectures and took detailed notes, even binding them and sending a copy to Davy. This resulted in Davy asking Faraday to take notes for him after Davy had been after an experiment went wrong and he was unable to write for a short while.

Faraday was so enthralled by all the scientific experiments that he started to experiment himself, building a voltaic battery and decomposing several salts in the manner that Sir Humphrey Davy had done.

Later that year he applied to Davy for a position but Davy had no vacancies. However early in 1813 Davy's Chemical Assistant was involved in a fight in the main lecture theatre of the Royal Institution and was dismissed. Davy remembered Faraday and invited him in for an interview, after which he offered him the position.

Initially Michael Faraday worked under Davy, and later under Davy's replacement, William Brande. However between 1813 and 1815 he accompanied Davy as his assistant on a scientific tour of the continent. As Britain and France were at war, permission had to be obtained from Napoleon himself. This granted they set off on their travels around Europe, visiting Paris, Italy, Switzerland, Athens and Constantinople. On their travels they met with Andre Marie Ampere in Paris and the ageing Alessandro Volta in Milan. On their return to England in April 1815 Michael Faraday resumed his position at the Royal Institution.

Although the tour had been a great success in many ways, it had not all been enjoyable as he had been expected to be a personal servant for Davy and also his wife who did not treat Faraday particularly well.

Turning to electricity

In 1820 the Danish philosopher Hans Christian Oersted discovered electro-magnetism. He had shown that when an electric current was passed through a wire close to a pivoted magnetic needle, it was deflected, indicating that the current flowing caused a magnetic field to be set up.

Faraday took an interest in Oersteds discovery because at this time, electricity was considered to be allied to chemistry. He made some further investigations. In one experiment undertook in 1821 he passed a current through a wire that was in the magnetic field from a strong horseshoe magnet and discovered that the wire moved. Although obvious today, this was a major milestone in the understanding of electricity and magnetism and brought him considerable renown. This meant the way was now open to create mechanical motion from magnetism and an electric current.

After this Michael Faraday returned to his chemical researches and it would not be for another ten years that he would make any further contributions to electrical science. In 1823 he succeeded in liquefying chlorine, and then in 1825 he discovered a chemical he called "bicarbuet of hydrogen" but known today as benzene. He also spent many years making and investigating optical glass.

From the days when he had attended the City Philosophical Society, Faraday had always enjoyed lectures. He was also a very gifted lecturer himself, and he believed in sharing his knowledge and wonder of the science of his surroundings. Accordingly in 1826 he founded the Friday Evening Discourse, and later that year he commenced the Christmas Lectures. Both of these continue to this day, the Christmas lectures being televised. Faraday actively participated in both, giving a total of 123 Friday Discourses and 19 Christmas lectures.

Whenever Faraday lectured, the auditorium was full, indicating his immense popularity and like many of his other achievements it was the result of much practice and effort. However it was recorded in one lecture that an elderly gentleman in the front row fell asleep and snored loudly. Faraday paused and some clapping gradually broke out. The elderly gentleman awoke and joined in the applause to everyone's amusement. Faraday then resumed his discourse.

Electro-magnetic work resumes

Although Faraday's work had focussed upon other researches, the idea of electromagnetism had never been far from his mind. Indeed his notes from 1821 contain the words "Convert magnetism into electricity", and he had periodically performed a few experiments during the following years, but without any success. Then in 1831 he completely focussed his efforts on electromagnetism. In just ten days he succeeded in discovering the principles of electromagnetic induction, although he refined the work for some years afterwards. Until this time, people had thought that a magnetic force could be changed into electricity. It was Michael Faraday who demonstrated that the magnetic flux around a wire had to change before any induced current flowed.

Although Oerstedt and others had shown that an electric current could produce a magnetic field, Faraday was able to demonstrate the reverse where magnets in motion in the proximity of a conductor could produce an electric current.

His most famous experiment consisted of a ferrite ring on which there were two separate windings of insulated wire. A battery was connected to one, and a galvanometer to the other. Only when the battery was connected or disconnected did the galvanometer deflect. In a second experiment Faraday placed a rotating copper disk between the poles of a large permanent magnet. He showed that a current could be obtained in a conductor that extended from the axis of the disk to its edge.

In some experiments with static electricity he developed a similar idea of electric lines of force and he undertook many experiment's concerning dielectrics and non-conducting materials. Out of this work he developed the idea of what he called the specific inductive capacity, or what we know today as the dielectric constant.

It was also during this period, 1832 - 1834, to be exact, that Faraday undertook his work on electrochemical action. He coined the words loved by schoolboys of electrode, cathode, anode and ion to name but five.

The work on electromagnetism and electrostatics was at the forefront of his work for most of the time, and he put himself under considerable pressure to complete it. Unfortunately this took its toll on his health and coupled with the fact that he also became an elder in his church, there was a sharp decline in the level of his research work and his lecturing in the early 1840s.

Work restarts

Around 1844 Michael Faraday commenced another period of work. This was to be his last, and the main discovery was that he was able to rotate the plane of polarisation of light passing through some heavy glass that was in the magnetic field from a powerful electromagnet. When the electromagnet was turned on and off the state of the polarisation of the light changed.

With these and other observations, Faraday delivered a major lecture in April 1846 entitled "Thoughts on Ray-vibrations". This set the basis for Faraday's theory of electromagnetism he developed in the following years. This work was later taken up by James Clerk Maxwell who developed his famous equations that describe electromagnetic waves which in turn lead to the physical discovery of radio waves.

Faraday's final years

In view of his tremendous contribution to science Queen Victoria, the British Monarch offered him a grace and favour cottage at Hampton Court in 1858 which he accepted. He was also offered a knighthood which he declined.

With advancing age, ill health took its toll and he suffered from many of the issues associated with dementia. His powers of reasoning were not as good as they had been and he suffered from loss of memory.

Realising that he could not keep up his original pace of work he began to retire from his many commitments from about 1860. Although still interested in science, he contented himself with a quieter life. However six years later in 1864 he was offered the presidency of the Royal institution. A humble man he was shocked that he would even be considered for the post and declined.

Sadly, Faraday died three years later on 25th August 1867 and was buried in the Sandemanian plot in Highgate Cemetery alongside his wife Sarah. During his life he had turned down the offer of a place of burial in Westminster Abbey. An honour which is reserved for only the very greatest of people within British society - kings, queens and Isaac Newton is also buried there.

Faraday remembered

He is famous for the immense number of discoveries he made and their importance yet he was also humble, taking his Christian faith very seriously. In doing this he donated a portion of his income to the church and also spent time visiting the sick.

He was also a warm character, but on some occasions he could be fiery. He generally kept his temper under control, channelling it into his work where it manifest itself in a truly remarkable level of output. He also had a good sense of humour. Once when he was explaining a discovery to Gladstone who was Chancellor at the time he was asked, "But after all what use is it?" Faraday quickly responded saying, "Why sir, there is every probability you will be able to tax it."

Today Michael Faraday is fittingly remembered as a truly remarkable scientist. Working tirelessly on little more than a wooden bench with crude instruments he opened up many of the fundamental laws of electrical science. He also had the rare gift of true genius combined with the ability to describe his ideas clearly and to enthuse others.

Fittingly the unit of capacitance is named after him as a tribute. The term "farad" was initially used by Latimer Clark and Charles Bright in 1861 as a unit of charge, and later as the unit of capacitance. Then the International Congress of Electricians officially adopted the farad as the unit of capacitance at their congress held in Paris in 1881.

Today, Michael Faraday is remembered as a true genius - one of the great pioneers in science along with the likes of Newton and many others - a real achievement for someone with little formal education.

Written by Ian Poole .

Written by Ian Poole .

Experienced electronics engineer and author.

More Famous Scientists in Electronics and Radio:

Volta

Ampere

Armstrong

Appleton

Babbage

Bardeen

Brattain

Edison

Faraday

R A Fessenden

Fleming

Heaviside

Hertz

Ohm

Oersted

Gauss

Hedy Lamarr

Lodge

Marconi

Maxwell

Morse

H J Round

Shockley

Tesla

Return to History menu . . .